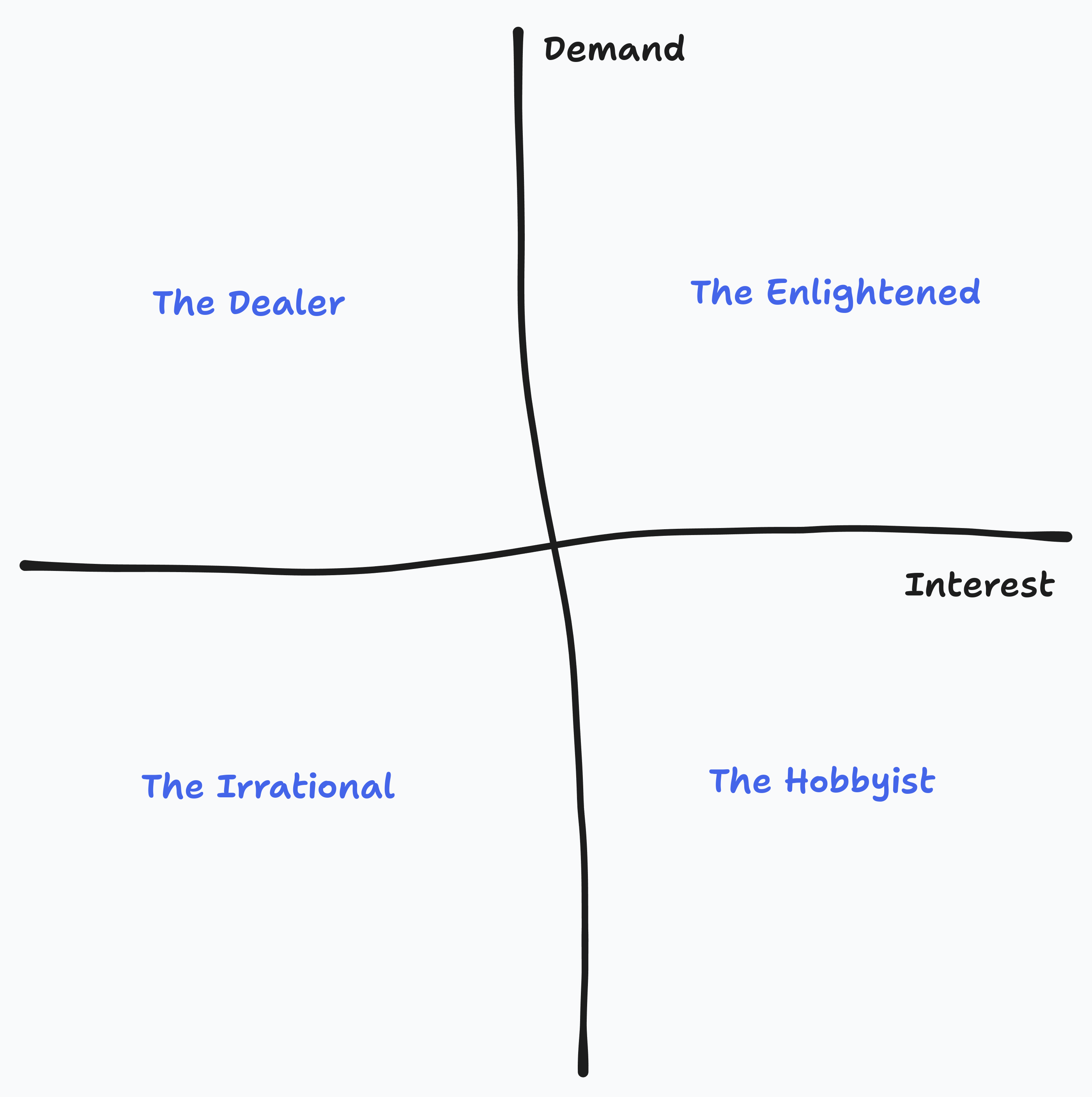

The 4 quadrants of founder-market-fit

I’ve found that intense interest in any subject is indispensable if you’re really going to excel. — Charlie Munger

As a founder, when you are starting a business, you have to think about what market do you want to focus on. This also happens if you haven’t yet achieved the nirvana of startups, the product-market fit, and you need to pivot your product, market or both.

Also, usually before product-market fit, as you don’t have a huge budget, your resource allocation (time, money, or both) for experiments is very restricted.

People, especially VCs, suggest you to follow market trends. Sometimes these trends are impulsed by the demand, but other times the supply side is what drives them.

Following the demand is good, but in my opinion, and what I want to remark here, viewing only from the demand side, is just a single variable of the equation.

The other side, which is usually neglected when you have less experience starting a business, is pursuing also something that motivates you. A product (and problem) in which you have an intense interest, as Charlie Munger said.

Considering both variables, the demand and your interest, is where the magic happens. When we have one, but not the other, the four quadrants emerge.

Let’s start thinking about these different scenarios.

Starting with the simple one. Not having a demand and not having any interest in that market or product.

This quadrant is very easy to reject.

If you are building a product that doesn’t give you any joy and the demand doesn’t exist, you must consider what you are doing. I call this quadrant the irrational founder.

Next one, building something that interests you, but without any demand for it.

This scenario, which I call the hobbyist, happens when you pursue the common statement: “Follow your passion”

Passion for something is not sufficient to build a business. In order to have a business, you need people who want to pay for your product. Without what are usually called customers, you don’t have a business.

It’s worth remembering that you will never capture the whole market.

If you can capture any portion of the market at all, the most probable scenario is a very small percentage of it. So if the market size is small, your business won’t be able to sustain its operations with its tiny market share.

What makes it hard to stop being in this quadrant is that doing something you like is very addictive. Everyone wants to work doing something they like.

And that can lead to lying to yourself. To not seeing the signals that the market is giving us. Small amount of sales per month, small traffic. Even though you tried different experiments and different distribution channels, the demand doesn’t respond to your product.

Also, having some amount of revenue can be a huge curse. It can prevent you from finally throwing the towel. But at some point you have to go back to the blackboard:

- Is there a market at all for this?

- And if it’s there, what size is it ?

- Is it growing, is it stale, or is it shrinking?

The next quadrant, is the one that I call the Dealer.

A lot of business people that I met are in this quadrant. They don’t care what they are building or how they can improve their customers’ expectations. They just want to see the numbers on the spreadsheet grow.

I don’t have any problem with that, this essay doesn’t want to make any moral claims. The problem with this quadrant is that without a real (and intense) interest, it’s hard to have a competitive advantage. To have an edge.

If there are other founders trying to reach the same market (and if the market is growing and with high returns, you can be certain that there will be) and they are more motivated than you in solving that problem, it would be very hard to compete with them.

You will tend to become a follower, not leading any innovation or any differentiation. This might not bother you because you are making money, you are growing.

But when growth stagnates, and you need to improve the product and look for other revenue sources, you will feel empty.

You will start with existential questions like: This isn’t fun, why I am doing this? And then you will realize that closing (or exiting) a medium business is harder than closing a smaller one.

There will be customers that would want to keep using your service. You will have employees that would depend on their monthly salary.

You will think about selling your business, but finding a buyer will be hard because it wouldn’t be growing anymore. And if you found one, you would feel insulted by the price they would want to pay for the business you have worked so hard to build.

Markets are dynamic, there are times when you will grow and there are times when you will need to shrink. Adaptation is the key. In order to be able to reduce and adapt, financial motivation is not enough.

Then comes the last quadrant. The enlightened one. Doing something you love and something the market is demanding. And with a market size that can sustain the business you want to make.

If you are here, you are in a very good position, dear reader. You will be able to keep improving your business when the market stagnates. You can keep doing what you like without any goal. You already achieved building a business that can sustain you and your lifestyle.

But everything in life comes with a price. There is a caveat. Life is dynamic. Your tastes can change.

Something that you loved doing, you might hate it in the future. Musicians usually hate playing the song that made them rich. Or they want to try new genres that their fans don’t like.

There is a quote: “What brought you here, won’t take you there”.

You liked doing the things that brought your business to the current stage. But if you have pressure to keep growing (because the competition is ruthless, or because your VCs need higher returns, etc.), you might not like doing the things you need to do to reach the next step. Your business expects you to grow with it.

A personal confession. As a technical and product executive, I don’t like managing huge teams. I don’t like being a full-time manager.

I like building software products. I like being in the trenches. With a huge team, you are very far from the solution and from the customer problems.

So in order to keep doing what I like and be able to keep the business growing pace, I needed to choose a tech stack with which a small team can deliver quality work in a reasonable time.

Thankfully, in my company, Nulinga, we use Ruby on Rails, a framework that I love very much to use. Also, in my (very biased) opinion, Ruby is the best language a developer that aims for happiness can use.

Back to the last quadrant, and the last warning here, the market might take a direction that you no longer feel interested in pursuing.

You might like to build a solution that helps professionals. And, in order to build it, you enjoy talking with them, understanding their struggles and their goals.

However, if a new technology that could remove those professionals’ jobs emerges, then you won’t like the direction the market is going. And that’s alright. You have permission to say that isn’t something you want to keep working on.

There can be other opportunities, other problems to be solved.

The best you can do is to keep exploring. New frontiers, new markets, and new activities that you love doing can appear.

The only way to discover them is to keep doing. To try new things.

Always keep experimenting.